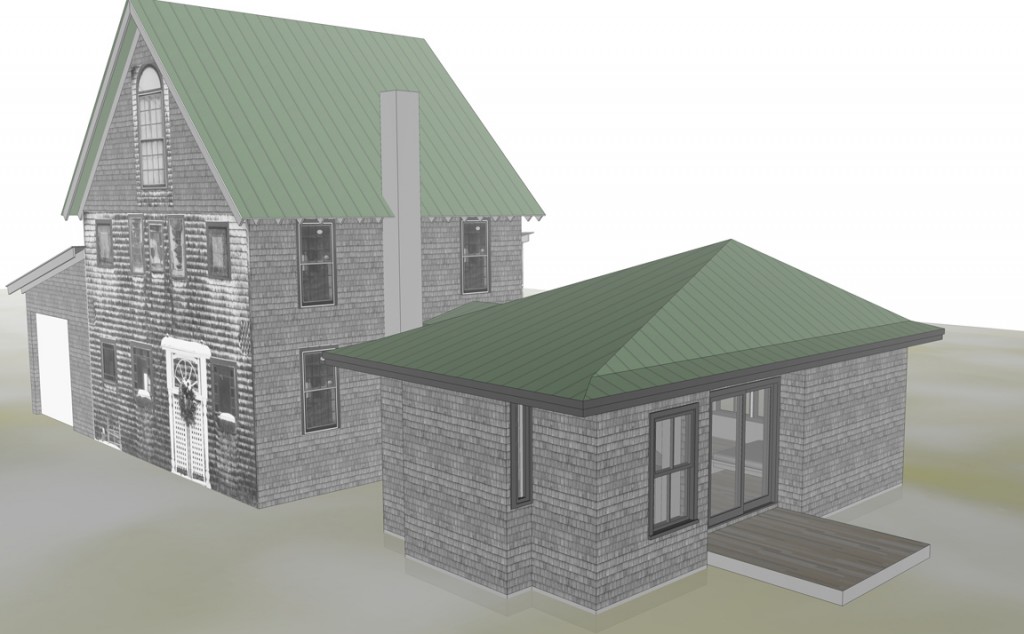

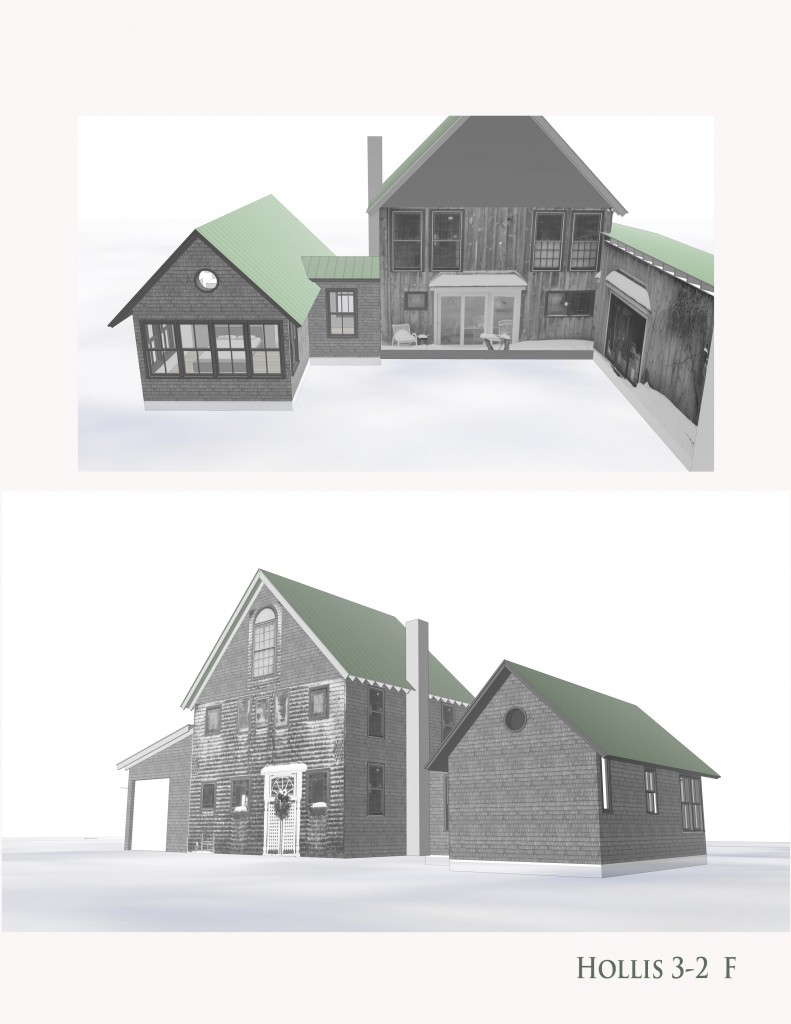

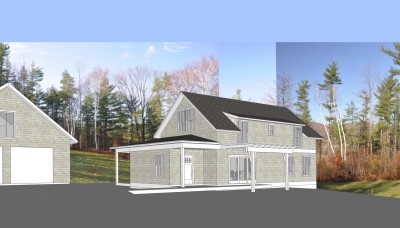

I am working on this new small greek revival in Maine. Not the high style Greek Revival with huge columns like you see on banks and government buildings but the small, simple style that is so ubiquitous in New England and doesn't get much attention but everybody knows. I'm designing it to "pretty good house" standards. It is for a family member who lost her house in a fire- we'll see how the budget goes and if the details get watered down as is often the case. She has always loved the Greek Revival look which is more often done wrong than right it seems. I used this sketchup model to push and pull and play with trim and proportion to get it right. I have found that often the frieze board (the wide flat board at the top of the siding under the eaves) often gets shortchanged when the builder frames the house including window openings then discovers that he doesn't have enough room for a properly proportioned frieze.

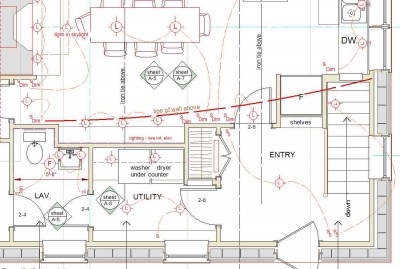

In any design there is always a lot of back and forth on windows - what works inside may not be so great on the outside etc. so I use the model to really fine tune it in terms of balance, rhythm, symmetry/asymmetry (exterior aesthetics) and light, cross ventilation, views, sun and solar gain, the feel of the room, (function and interior aesthetics)

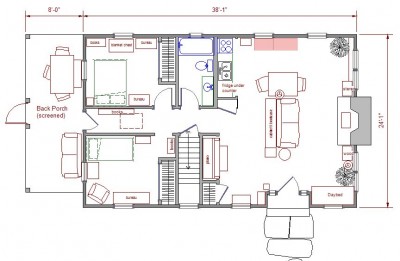

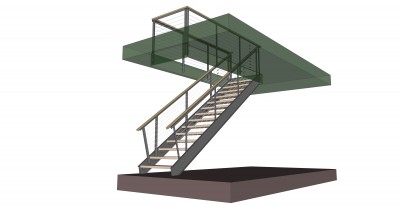

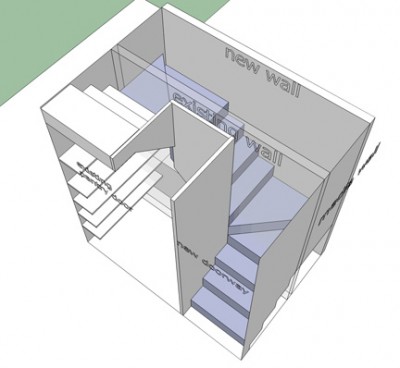

This is very different from this house which is currently under construction in Vermont which is also a "Pretty Good House" although nearly to the Passive House with Unilux triple glazed windows from Germany But with a modern aesthetic and some really beautiful spaces and materials. We are using raw green 1 x 3 hemlock from a local mill at siding over coravent strapping (rain screen detail) and Mento 1000 weather barrier. The hemlock will dry in place, turn grey and gap in a rougher version of open joint siding often created with Ipe or cedar siding.

I am also studying and reviewing the first three days of Passive House training. The next three days are coming up next week. I am learning a lot of building science stuff that will improve the level of design and service I am able to provide - whether or not I ever get to work on a certified passive house. It was disconcerting, however, to ride the bus into Boston past thousands upon thousands of older houses and housing stock that is rather the opposite of Passive House in terms of energy usage and all the other metrics. You get the feeling of "what's the point". Is passive house a just another trophy for someone building a new house to attain and meaningless in terms of saving ourselves from the coming death, doom and destruction of climate change? I am looking at it in terms of simply building better houses and not thinking about saving the world.

"No matter how many times you save the world, it always manages to get back in jeopardy again. Sometimes I just want it to stay saved, you know? " - Mr Incredible.