Bluetime Collaborative:

I just attended a mini seminar at Building Green with Peter Yost on wall and roof systems - moisture management. something of a recap for me but what I think about are how many architects and builders are still doing things the way they were 10 or 20 years ago.

Bluetime Collaborative: I think what I got out of it was that we need to think more in terms of systems rather than simply products. There is a huge amount of information and discussion out there that most builders and architects are ignoring at their own peril.

Bluetime Collaborative: Remember building is a science, codes represent bare minimums and are always ten years behind the science, r-value is but a small part of a system

Dave:

Bob, what is their wall/roof system recommendation?

Bluetime Collaborative:

it boils down to air and moisture management and dealing with them as separate issues. ideal systems may differ from practical systems. (what would you do on your own house -vs-what would you design for someone else to build. Always know where your dew point will be to prevent failures. (LOTS of failures in the northeast in recent years) walls need to dry to the inside and outside. Air condiitoning introduces a whole new set of parameters. Boston based Building Science Corp is a good place to start. Insulation is what you add when everything else is done right. Systems management means there are tons of great and products out there and tons of hype, but little knowledge of how to put them all together as a system to minimize risk. Have a lawyer design your details ;-) they will research the science and design no minimize risk. Or design like a lawyer...

Dave: What's the current though on closed-cell foam? I like what it does for creating a very tight envelope but question what happens when water works its way into the wall. Open cell scares me - I have seen it blacken with mold because of infiltration at a roof.

Bluetime Collaborative :

worth further investigation I would check greenbuildingadvisor.com - I have been lucky to never have used open cell. I hear it isn't great. I have used closed cell in a flash and batt situation often. It works very well with my double stud wall system and has lots of advantages. The key seems to be to flash thick enough so the dew point doesn't happen at the sheathing and look at the overall wall in terms of how it can dry out. (always assume things will get wet) For instance; vinyl wallpaper doesn't allow for drying to the inside.

Dave : Fine Homebuilding just had an article on the flash and batt approach. I was apprehensive when I read it thinking it would only be marginally more to fully spray the walls. I'm hoping to do closed cell on our house but it will come down to a budget decision.

Bluetime Collaborative:

Flash and batt is usually cheaper enough to make the decision clear. A timing advantage in the fall is that you can flash, then all the subs do their thing in a warm heatable environment then fill in right before sheetrock. Probably the best performing system involves 2" of rigid outside (depending on where you live) with cellulose inside but detailing is tough - learning curve. Window manuf. are now adding exterior jamb extensions to their options.

Dave: I've seen that exterior insulation detail in Building Science Corp's books but have never done it before. Flash and cellulose is an interesting combination.

Matt :

Bob, which window manufacturers? Thermotec? Also, this is a killer blog entry. I'm not buying flash & batt at all, especially with less than 2" flash coats; flash & pack ... maybe... better continuity, fewer gaps, between the lumpy foam and the cellulose than batts. I can't agree more on the theme of systems over products. I do construction estimating for a building supply company. I see 8-10 plans a week. The scariest thing I see right now is a la cart use of new products without regard to the system.

Matt: Actual construction document examples: taped 1" XPS over taped ZipWall with 5" cavity OPEN CELL, continuous Grace Ice & Water shield over closed-cell rafter bay insulation (Grace has even published a report advising against this), and 9" rafter bay closed-cell under a flat roof (mostly egregious because there are a dozen known more practical ways to deal with that).

Bluetime Collaborative: yikes!

Bluetime Collaborative: I should clarify and perhaps my terminology is wrong. By "Batt" I do mean a blown in dense pack cellulose or even fiberglass not batts. Does anybody use those anymore? (sarcasm)

Bluetime Collaborative: When I look back over the past ten years at my own work I see an interesting progression from 2 x 6 walls with fiberglass batts, poly vapor barrier and no questions asked to now where each house I do is a bit different and I spend much time investigating the options including what I can sell to the owner and what the contractor will actually build as well as what the budget will allow.

Dave: Bob - What is your "ideal" wall and roof system?

Bluetime Collaborative: as of today or what will it be next week? performance wise all foam on the outside with an empty 2 x 4 wall cavity inside.

Bluetime Collaborative: practical (cost /benefit analysis) double 2 x 4 stud 8 to 10" deep with 1 1/2" foam outside taped. up and over the roof if possible too.

Dave: With that much foam outside how to you detail door and window penetrations economically?

Bluetime Collaborative:

that was my ideal performance scheme - not cost effective or very easy to detail. you see it sometimes on European passive house projects, often with the windows set to the inside face of the wall for increased thermal performance. Practical is 1 1/2" xps foam outside, (1" doesn't get the dew point out of the sheathing) and dense pack cellulose in the cavity. The question then becomes whether to set the windows and doors to the sheathing or block them out to the outside of the foam and strapping. (complicated layering and flashing) fortunately some window manufacturers are addressing this as I mentioned before with exterior jamb extensions. I also have a detail to allow an inswing exterior door to be mounted to the outside but still open nearly all the way. You can see it in the "Tiny House Plan for Sale"

Matt: Dave, if you want to see details on the 'all outside the wall' insulation plan you can download the REMOTE wall manual or look into the Canadian PERSIST method.

Matt: http://www.cchrc.org/

Bluetime Collaborative: foam on the outside works to get the dew point away from the sheathing but what about the ability of the wall to dry to the outside? I still have too many questions. I'm going to find a building scientist, knock him down and sit on his chest until he (or she) tells me what to do.

I hear you on that. One question: how do you figure out where dew point occurs for various times of the year within a wall?

Bluetime Collaborative :

I think they look at the average temperature for the three coldest months (I could be wrong) because if the dew point occurs before the sheathing, water condenses on the sheathing itself and ices up rather than drying out. This is often a p...See More

Rui :

good chat! With IBC 2009, the exterior wall design comes into question FINALLY, but only because the R-value is bumped up to 20 or (13+5). With the very first opportunity we had, we went with batt stud cavity R-13 insulation and R-5 continu...See More

Bluetime Collaborative :

In VT and much of northern New England only 1" of ext foam puts the dew point in the sheathing too much of the time (rot issues) so we go with 1 1/2 to 2". Nominal vs actual doesn't seem to make it into codes either. a 2 x 6 wall with fib...See More

Rui: well that was exactly my next set of comments, the codes only go so far. Understanding the wall technology is more important than prescribed R values.

Bluetime Collaborative: reading...reading....

Dave: This is going to make a great blog post. I've been thinking about the wall section you sent for the last few days. I've also been thinking about this at a time where I'm detailing my own house. It's giving me a headache.

Bluetime Collaborative: Luckily we have GBA which has really become The on stop shop for learning. When I go to seminars for cont ed. it is all repeats of the discussions on GBA. Feel free to add questions you have, Environmental Building News is 1/2 mile away from my office - I have some contacts. http://www.energysmiths.com/ - Marc Rosenbaum is an excellent resource as well.

Dave: I'm scared of what the answers could be but I'm wondering about red cedars (non-rainscreen) over Zip System with closed cell poly (2x6 construction) and no vapor permeable membrane and an interior of veneer plaster. This is our standard wall these days...

Rui?:"Vaproshield" barrier

Bluetime Collaborative :

vaproshield is an excellent product and what you use for an open rainscreen. I would look seriously at a rainscreen detail even just bumpy tevek type stuff. Rainscreen detailing is becoming code in parts of this country and if you did wood siding in some northern euro countries without rainscreen, they would look at you like you had two heads. I think the cedar works in your favor. We sometimes use New England white cedar from our local mill.

Greg: I am really not enthusiastic about the addition of low perm foam in thick layers to a wall system. Once you do this, you reverse to a drying to the inside wall system, and now suddenly every micro-climate needs to check the dew point location of their wall configuration to avert a disaster. To me this just does not make sense. A dry to the outside wall system is something that works over a wide climate range, and if AC is introduced, a smart vapor retarder like Membrain allows you to balance the drying performance for the summer.

Bluetime Collaborative: I'm starting toward the no foam on the outside idea as well. simply due to the drying thing. A local builder is liking Membrane and I tagged it elswhere for further study. We are lucky in VT as only people from out-of-state who build houses here seem to want A.C. We do seem to have extended very wet times (like now) every summer. I keep coming back to my oversimplified double stud wall for simplicity and low cost and excellent thermal performance. I've done it 1/2 doz times so far with different builders so the kinks are mostly worked out. Think of the inside 2 x 4 wall as just another interior wall.

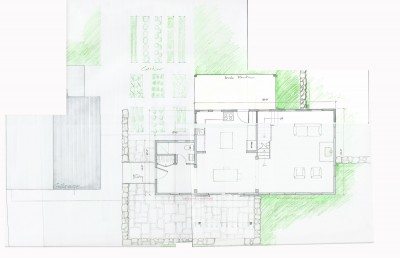

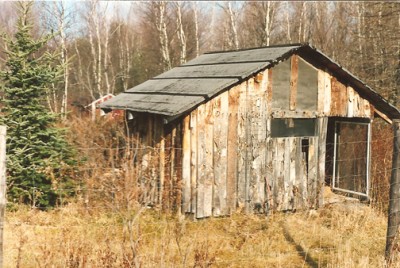

Anyone can draw up a floor plan right? well....

Drawing a a floor plan is more complicated than most people realize.

Anyone can draw up a floor plan right? well....

Drawing a a floor plan is more complicated than most people realize.